Civil administration in Sudan: is it the only way out of the spiral of collapse?

At the heart of Sudan’s prolonged tragedy, as state institutions and essential services crumble at an accelerating pace, an unavoidable question emerges: can a country exhausted by war, where the very notion of the state has faded, recover without establishing a strong and professional civil administration? This investigation delves into the core of the issue, drawing on testimonies from former government employees, public administration experts, and multiple documents, to reveal that the essence of Sudan’s crisis lies not only in the war, but in the absence of a civilian system capable of ensuring the state’s survival and functioning.

Government documents we obtained, along with reports by international organizations, clearly show that nearly sixty percent of civil-service institutions were operating with less than half their staff even before the latest war, due to politicization, administrative stagnation, and poor training. As fighting expanded, water, health, and education administrations collapsed in most states, and qualified technical staff left their posts, leaving the country facing an unprecedented institutional vacuum.

A former employee of the Ministry of Infrastructure, who asked to remain anonymous, says the problem goes far beyond a lack of funding or equipment. He explains that the absence of a professional operating system was the most dangerous factor: stations and facilities managed through political loyalties rather than technical standards did not withstand more than a few weeks of instability. This account aligns with internal UN reports confirming that Sudan’s service collapse is directly linked to the lack of stable civilian institutions with clear structures and fixed operating systems, and that the war merely exposed what had long been hidden.

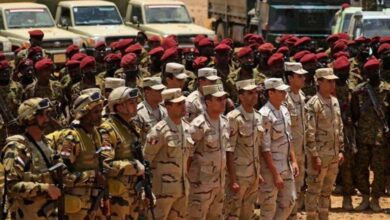

Field interviews across several states also indicate that military forces, in all their forms, attempted to fill the gap by managing electricity networks, water systems, and hospitals — efforts that quickly proved unsuccessful. Soldiers are not trained to manage budgets, run stations, or supervise complex logistical systems. A crisis-management professor at the University of Khartoum notes that armies may impose control on the ground, but they cannot run a modern state, which requires engineers, financial experts, administrators, accountants, and maintenance and operations contracts, not military orders.

A review of records from eleven states shows that seventy percent of public-service administrations relied on individual decisions or emergency committees before the war instead of institutional systems, meaning the state’s collapse began years earlier, with the war merely completing the process.

Despite the bleak picture, several rare field experiences demonstrate that professional civil administration can succeed even under the harshest circumstances. In Gedaref State, for example, the water management unit was able, between 2022 and 2024, to operate eighty percent of its stations by separating technical work from political influence and implementing a digital monitoring system. In Port Sudan, groups of doctors and administrators managed hospitals efficiently despite the absence of direct government support, and attracted funding from international organizations because their administration was professional and data-driven. These examples show that Sudan’s broader collapse is not due to the impossibility of civil administration during wartime, but to the absence of institutions capable of functioning properly.

An analysis of why military solutions fail shows that the issue is not only that armies cannot manage services, but that military logic itself is not designed for state-building. Documents obtained from the Ministry of Finance for 2023 reveal that seventy-eight percent of spending went to the security sector, while essential services received only eight percent, leaving the state unable to provide energy, water, or medicine. Military spending not only drained the budget but also prevented any possibility of economic development.

A study conducted by Sudanese economists in early 2024 indicates that the country loses thirty-five million dollars per day due to disrupted production, broken supply chains, and lack of resource oversight. The study argues that a professional civil administration could reduce these losses by forty percent within a single year through improved revenue collection, regulated exports, and activation of oversight institutions. Sudan’s economy — based on agriculture, mining, gold, and ports — depends entirely on institutions that manage resources, regulate markets, and monitor revenues. No military or tribal force can perform these functions.

All these testimonies and documents show that Sudan’s future depends on its ability to restore civil administration, not its ability to win the war. A state without professional institutions cannot restore services or build a sustainable economy, even if the fighting stopped tomorrow. Military solutions, though sometimes necessary to confront specific threats, lack the tools required for state recovery, while the few successful cases prove that civil administration, when professional, can endure and revive public life.

Ultimately, Sudan stands at a historic crossroads: either it rebuilds strong civilian institutions that ensure the continuity of services and economic recovery, or it remains trapped in a cycle of collapse, regardless of changes in the balance of power on the ground. Institutional civil governance is no longer a political option but an existential necessity for the state’s survival.