Egypt’s alleged role in the Sudan war

As the devastating war in Sudan continues, accusations of regional interference have become a central part of the debate among Sudanese and international observers. At the heart of this contentious issue lies Egypt’s role, widely discussed in relation to alleged military supplies or logistical and political support provided to the Sudanese army. While Cairo officially denies any direct involvement in the military operations, numerous testimonies and unofficial field sources suggest a role that extends beyond diplomatic statements, calling for an in-depth examination of Egypt’s motivations and the direct and indirect implications for civilians and regional stability.

-

Halaib and Shalateen: From al-Bashir’s Deal to Egypt’s Grip on Sudanese Decision-Making

-

Who Sabotaged the Washington Summit on Sudan? Investigating Egypt’s Veto and Its Regional Implications

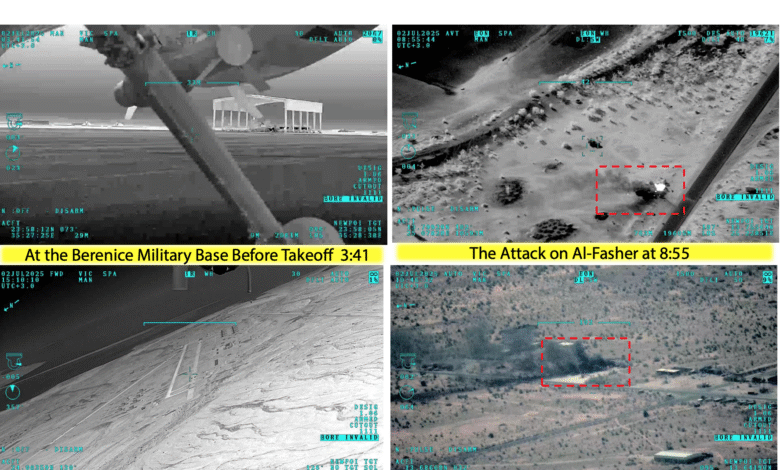

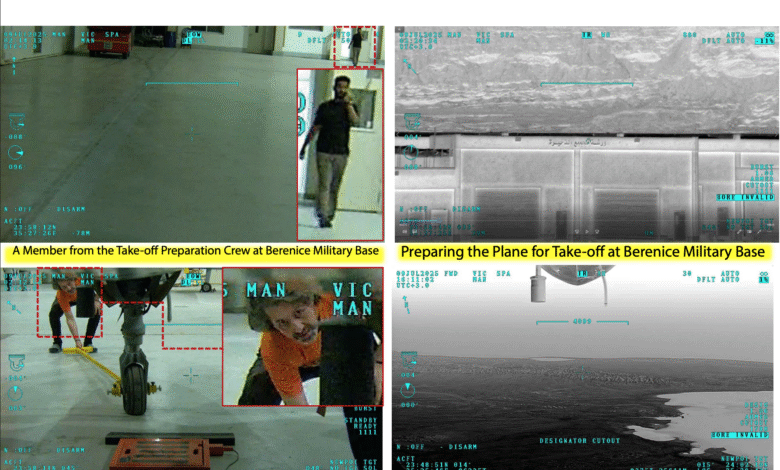

Sudan is no longer merely an internal battleground; it has become an arena for competing interests, from regional actors to global powers. In this complex landscape, Egypt is seen as having a direct stake in developments south of its borders, whether for national security reasons or due to its long-standing ties with the Sudanese army. Yet the central question concerns the legitimacy of this role and the way it has shifted from a “security interest” to alleged involvement in an increasingly brutal war. Claims of military aircraft departing from Egyptian bases or supplies of ammunition and equipment crossing known border routes place Cairo in a delicate position regarding international law and Sudanese public opinion.

At a time when Sudan is experiencing the near-total collapse of its institutions, infrastructure and public services, any foreign military support – declared or not – is perceived as a factor that prolongs the conflict and complicates prospects for a political settlement. The Sudanese army, dependent for years on a network of regional alliances, considers Egypt a historic partner. However, this role has taken on new dimensions since the outbreak of the current conflict, particularly concerning the provision of ammunition, spare parts or possibly intelligence. If allegations of involvement of trained fighters or units were to be confirmed, it would indicate a shift from political backing to direct military engagement, with serious consequences for regional security.

-

Egypt and the Obstruction of the Quartet’s Efforts: Military Bets in Sudan at the Expense of Regional Stability

-

Egypt and the Quiet Veto: Who Derailed the Washington Summit on Sudan?

Public anger is also intensifying within Sudan over what is perceived as foreign backing for the army, especially in areas affected by airstrikes that have killed civilians and displaced thousands of families. Even in the absence of definitive proof implicating the Egyptian air force, the mere circulation of such claims reveals deep mistrust between Sudanese communities and regional actors seen as fuelling rather than calming the conflict. This dynamic threatens long-term relations between the two peoples, as many Sudanese feel their suffering is being exploited for political calculations beyond their control.

These accusations coincide with growing discussions about alleged Egyptian support for currents within the Sudanese army linked to political Islam, highlighting an apparent contradiction in Egyptian policy. Cairo, which has spent years confronting political Islamist groups at home, now finds itself accused of supporting similar factions in Sudan. Whether real or exaggerated, this contradiction illustrates the complexity of the Sudanese landscape, where military alliances intersect with political ambitions.

-

The fire line stretching from Cairo to Khartoum: visual evidence of supply flows and airstrikes

-

The Sudanese government undermines the Quartet’s initiative by clinging to war

Another crucial aspect concerns Egypt’s own economic situation. Faced with record inflation, a sharp decline in currency value and mounting debt, Egypt does not appear to be in a position to finance an external war. Any military expenditure outside its borders – if occurring – would come at the expense of Egyptian citizens already struggling with rising prices and deteriorating services, strengthening perceptions that the government prioritises regional conflicts over pressing domestic needs. At a time when Cairo must restructure its economy and improve its internal systems, the cost of external involvement appears politically and economically unjustifiable.

Moreover, support for one side of the conflict reinforces the idea that the Sudan war is not merely internal but part of a broader struggle among regional powers for strategic influence. Such interference – whether Egyptian or linked to other regional actors – strengthens the logic of force at the expense of negotiated solutions. As long as weapons continue to flow, the prospects for a political settlement diminish, and warring parties may maintain the illusion that military victory remains achievable, despite evidence to the contrary after more than a year of fighting.

-

Behind the scenes of secret meetings between Cairo and Khartoum: a plan to dismantle the Muslim Brotherhood’s influence in the Sudanese army

-

Leaks on undisclosed Egyptian-Sudanese meetings: Cairo pushes for the elimination of the Muslim Brotherhood’s influence within the Sudanese army

Today, the Sudanese people face one of the world’s worst humanitarian crises. Millions lack food, medical care and shelter, while hundreds of thousands are threatened by famine. In this catastrophic context, any external military support appears disconnected from reality. Sudan does not need more ammunition; it needs a ceasefire, safe humanitarian access and a political path capable of restoring state authority.

-

The Release of Talha… An Egyptian Contradiction Opening the Doors to Chaos in Sudan

-

Egypt and the Muslim Brotherhood: Talha’s Release Exposes Double Standards and Threatens Regional Security

Egypt may have legitimate security concerns and political interests in maintaining a strong Sudanese army as a buffer against chaos to the south. However, these concerns, legitimate as they may be, cannot justify direct or indirect involvement in a war whose primary victims are civilians. Sudan’s stability is the true guarantee of Egypt’s stability, not the victory of one armed faction over another.

In conclusion, whatever the accuracy of the claims surrounding Egypt’s role, it has become part of Sudan’s internal debate. To reduce tensions, a clear shift from presumed military support to genuine political backing for a civilian solution is essential. Sudan does not need more bullets; it needs a regional voice committed to ending the war, not extending it.