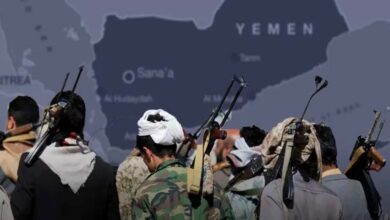

Floating cemetery: Houthi mines are killing Yemeni fishermen

From the shore to the open sea, the Red Sea is becoming a “floating cemetery” for Yemeni fishermen. Since 2015, naval mines laid by Houthi militias have been killing seafarers day after day, repeatedly inflicting tragedies on Yemeni families. Their small boats sometimes strike drifting explosive devices without warning, and in an instant the modest hope of a day’s catch to feed a family is shattered. The most recent catastrophe off Kamaran Island underscores that Yemeni fishermen are bearing the heaviest toll of the Houthi militias’ lethal presence at sea.

-

Houthis detain UN staff, including UNICEF representative

-

The Deluge toll: 1,000 Houthis killed in 19 months

What do we know about the latest incident?

The most recent tragedy killed three members of the same fishing family on Friday, when a naval mine planted by Iran-backed Houthi militias detonated in the waters around Kamaran Island, north of Al Hudaydah governorate in western Yemen. A government source said that a mine, blown ashore by the wind onto an exposed beach of Kamaran, exploded with a deafening blast while fishermen were searching for their daily catch. Walid al-Qudaimi, the governorate’s senior official, identified the three victims as Naeim Abdo Dom, Aslam Abdo Dom and Issa Basili, who were killed while fishing near Kamaran Island.

First such fatality since the truce

The death of these fishermen is the first recorded maritime mine fatality since the UN-brokered truce came into effect in April 2022, sounding the alarm about this continuing floating hazard. There is no comprehensive tally of victims of naval mines; human rights sources estimate that around 100 fishermen were killed during the first three years after the Houthis started deploying such mines — a deployment that began in 2015 and spread across the Red Sea, ports, islands and fishing coasts.

-

Between Denial and Confusion: Why Did the Houthis Delay Announcing Their Casualties?

-

Houthis redeploy military communication networks in Hodeidah

Since then, joint forces and the Saudi-led Arab coalition have discovered dozens of naval mines, some of them rudimentary and defective to the point that they do not remain anchored and become drifting explosive hazards.

What are drifting mines?

In recent years, clearance operations by the Arab coalition, joint forces and the Yemeni army have revealed that the Houthis used at least three types of naval mines, scattered indiscriminately in the Red Sea. The most widely used is the so-called “primitive mine,” roughly the size of a domestic gas cylinder and produced in various sizes; the militants use multiple local names for it. In addition, there are two Iranian models, often referred to as “Sadaf” and “Qa’a” (or “Qaa’”).

-

62 Years since October 14… A memory inspiring Yemenis in confronting the Houthi coup

-

Al-Hassan al-Murani: the Houthi operative weaving the militia’s web of alliances in the depths of terrorism

The primitive Houthi mine is particularly dangerous: it is anchored to a metal base so that it sits at roughly two metres depth, but when its moorings break it becomes a floating bomb. Military experts said that such mines weigh between 40 and 70 kilograms and are fitted with two to four highly sensitive detonators that explode on contact with any maritime object. The effectiveness and hazard of these devices depend on the quality of their metal casing and battery; if not dismantled they can remain active for six to ten years, posing a long-term threat to fishermen and shipping lanes.

The human and economic toll is severe: beyond the loss of life, these mines cripple entire communities, undermine livelihoods and make any maritime activity in the area perilous.