New Intelligence Law Brings Sudan’s Brotherhood Crimes to the Forefront

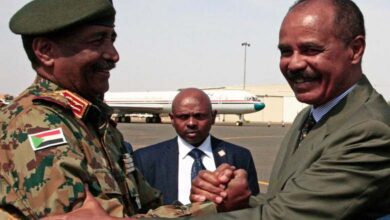

The amendments made by Sudanese authorities to the General Intelligence Agency Law have sparked controversy among politicians, activists, and military experts, especially as these amendments have restored powers to the agency that were withdrawn after the fall of the Muslim Brotherhood regime.

According to legal expert Mouaz Hedra, “the current amendments have granted the General Intelligence Agency greater powers than those granted to it during the al-Bashir era.”

He stated to Alhurra website that “the most prominent amendments include granting the security agency powers of arrest, search, and detention, as well as approving the renewal of detention for extended periods.”

The legal expert pointed out that “the amendments have given those tasked with implementing these powers and tasks complete immunity, and it has become impossible to prosecute them, either civilly or criminally, without the consent of the Intelligence Agency director.”

He added, “Even if a death sentence is issued against a member of the intelligence agency, it will not be executed without the approval of the Sovereign Council President Abdel Fattah al-Burhan.”

Hedra argues that “al-Burhan and his supporting group aim to consolidate repressive authority and curb freedoms to continue ruling Sudan.”

He added that “the repression, arrests, and torture currently taking place are worse than what occurred during the al-Bashir era, and the most dangerous aspect is that they threaten social cohesion.”

In contrast, Rasha Awad, a leader in the Civil Democratic Forces Coordination (Tajamu), believes that “the amendments restrict public freedoms and entrench the persecution of voluntary activists and advocates for ending the war.”

She said in a press statement, “The amendments aim to narrow down civilian political forces because the war originally broke out to eliminate the December revolution that ousted the al-Bashir regime, and that is why we notice that their attacks on civilian forces are more ferocious than their attacks on the Rapid Support Forces.”

Awad emphasized that “the current government first reinstated the operations unit, the military arm of the intelligence service, which had been dissolved by the constitutional document, and now all powers have been fully restored for the intelligence service to become a political tool for remnants of the Islamic movement to restrict democratic civilian forces.”

She noted that “the amendments introduced the term ‘collaborators,’ a term that did not exist in the old intelligence service law,” and that “collaborators are individuals who are not officially affiliated with the service but are ordinary citizens who provide information to the service in exchange for financial compensation.”

She warned that “the future will be worse” and said, “Military intelligence and security forces were already restricting those calling for an end to the war, often arresting them on the pretext that they supported the Rapid Support Forces, to the extent that some died under torture.”

Sudanese and international human rights organizations accuse the security service under the al-Bashir regime of involvement in violations against activists, including detention, enforced disappearance, torture, and murder.

After the fall of the al-Bashir regime, several security service members were tried for killing protesters, including 11 officers and soldiers, but the sentences imposed on them were not executed due to their escape from prison.