The Invisible Hands: How Egypt’s Military Involvement in Sudan’s War Prolonged Civilian Suffering

Egypt’s role in the Sudanese war has taken on a new dimension in recent months, moving beyond the limits of the “usual political support” into a more complex and controversial phase. Reports of military supplies and aerial interventions have multiplied, even as Sudan’s crisis deepens and civilians find themselves trapped between two fires: Sudanese factions refusing to retreat, and foreign interventions that give the war new life instead of guiding it toward an end. Among these interventions, Egypt’s role stands out as one of the most influential, especially amid increasing claims of direct involvement through weapons, ammunition, air operations, and logistical support described as decisive in shaping the battles.

-

Egypt and Sudan: An Open Battle Against the Muslim Brotherhood’s Infiltration of the Sudanese Army

-

Egypt’s role in the Sudan war: a military intervention that prolongs the conflict and deepens the humanitarian tragedy

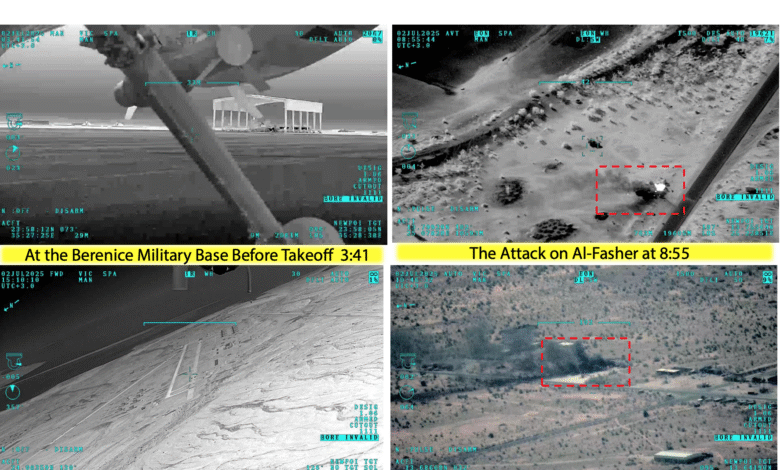

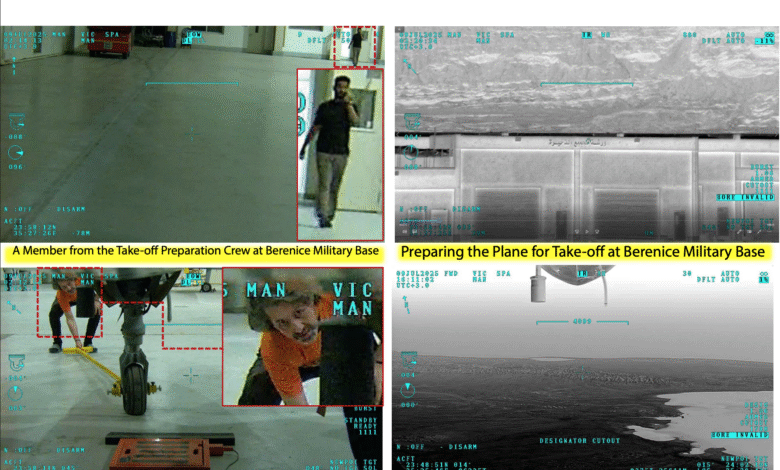

From the war’s early weeks, clear signs indicated that the Sudanese army was benefiting from unusual aerial support. Several airstrikes were carried out with precision exceeding the known capabilities of Sudan’s air force and coordinated with movements on the ground. This raised questions about who was directing or coordinating such operations. Numerous accounts described fighter jets operating from bases near the Egyptian border, while satellite images — though not conclusive — suggested unusual military activity in Egypt’s southern zones. These elements fueled the view that Egypt was no longer solely a political backer of Sudan’s military, but an actor engaged in the operational side of the conflict, either by conducting air missions or providing launching platforms for targeted operations.

-

Talha and the Controversial Release: Between Egypt’s Contradictory Discourse and Sudan’s Stability Crisis

-

The Egyptian Contradiction and Sudan’s Stability Crisis: When Ambiguity Opens the Door for the Muslim Brotherhood

Yet the impact of these strikes has not been purely military. The devastation left by some attacks on civilian areas sparked widespread outrage inside Sudan. Repeated bombings in densely populated neighbourhoods or areas presumed neutral have become common. Because the warring factions are embedded within residential districts, any airstrike — even one aimed at a military position — can quickly turn into a disaster for civilians. Destroyed homes, victims trapped under rubble, and streets echoing with panic have become part of daily life. Many Sudanese families now associate the increased intensity of bombings with foreign support to the army, seeing this aid as amplifying the tragedy and prolonging a war that civilians never chose.

Accusations also extend to disruptions of humanitarian convoys, a critical dimension of the conflict because it affects the survival of millions of people. In areas such as Darfur, Kordofan, and the outskirts of Khartoum, multiple incidents of attacks on trucks carrying food and medical supplies have been reported. Witnesses described aircraft flying at low altitude over convoys belonging to the World Food Programme or medical agencies shortly before these convoys were struck. Although no party has acknowledged responsibility, the timing of these attacks in relation to Sudanese army advances supports the theory of external aerial and intelligence assistance contributing to blocking humanitarian access.

-

Talha between Release and Impunity… Egypt Opens the Door to the Brotherhood Danger in Sudan

-

Halaib and Shalateen: From al-Bashir’s Deal to Egypt’s Grip on Sudanese Decision-Making

Suspicion also surrounds alleged arms-smuggling routes extending from Egypt into Sudan’s interior, used to transport ammunition and military equipment through difficult-to-monitor desert corridors. Sources claim that Egyptian weapons have surfaced in the hands of Sudanese army units, including artillery rounds and spare parts for heavy weaponry — items in severe shortage within the Sudanese military. If true, this would mean that Cairo is directly or indirectly positioned as a party to the conflict, sustaining a war led by a faction accused of extensive civilian abuses.

-

Who Sabotaged the Washington Summit on Sudan? Investigating Egypt’s Veto and Its Regional Implications

-

Egypt and the Obstruction of the Quartet’s Efforts: Military Bets in Sudan at the Expense of Regional Stability

The risks of Egypt’s involvement go beyond the military dimension, extending into the political sphere. The Sudanese armed forces have longstanding ties with influential Islamist networks, including groups linked to the ideology of the Muslim Brotherhood. These groups were part of Sudan’s governing landscape for decades and were associated with regional crises, including the unrest that shook Egypt in 2011. Supporting the Sudanese army — whether for stability or for border security — raises a fundamental question: does such backing indirectly empower Islamist currents that Egypt considers a strategic threat? This paradox has led many analysts to argue that Egypt risks recreating conditions similar to those that destabilised the region a decade ago, turning Sudan into a platform for ideological and political influence that could eventually undermine Egypt’s own stability.

Throughout this geopolitical interplay, the Sudanese civilian remains the primary victim. In the capital and in western regions, populations face severe shortages of food, water, and medicine. Some areas report deaths from hunger after months without aid. Meanwhile, civilians endure systematic abuses as a result of a war none of them wanted. Every foreign weapon entering Sudan and every missile launched from outside translates into more casualties, more displacement, and more destruction. The political horizon grows ever darker.

-

Egypt and the Quiet Veto: Who Derailed the Washington Summit on Sudan?

-

Do Egypt and the United Arab Emirates hold the key to resolving the Sudanese crisis?

This external involvement comes at a time when Egypt itself faces a severe economic crisis: spiralling inflation, a weakened currency, underfunded national projects, and rising public debt. In this context, many Egyptian citizens ask a simple question: why spend financial and logistical resources on an external war when Egypt’s domestic economy urgently needs them? This question has fuelled political and economic criticism, with many arguing that priority should go to education, healthcare, and internal development rather than military engagement beyond Egypt’s borders.

Ultimately, Egypt’s current role in Sudan’s war demands a fundamental reassessment. Sudan’s stability cannot be achieved through weapons but through pressure that pushes all parties toward inclusive political dialogue, a ceasefire, and safe humanitarian access. Egypt’s real interest lies not in prolonging the war but in preventing Sudan from collapsing into a militia-dominated vacuum that regional actors and ideological groups could exploit.

The current moment requires Cairo to rethink its approach to the Sudanese conflict, placing the protection of Sudanese civilians and the needs of the Egyptian people above all else. What the region needs is not more weapons, but political courage capable of stopping the bloodshed and preventing the region from sliding into an uncontrollable conflict.