The Invisible Hand of Cairo in Khartoum: Investigative Report on Egyptian Military Supplies

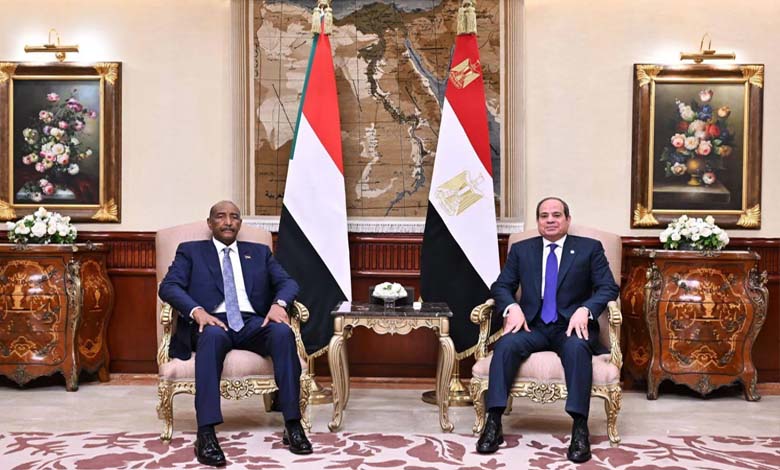

As Sudan undergoes one of its bloodiest and most divisive phases, new layers of regional interference are emerging, fueling the conflict and exacerbating civilian suffering. At the heart of these interventions, Egypt’s role extends beyond political or security positions to a complex network of military support, including weapons deliveries, facilitation of fighter movements, and airstrikes allegedly carried out by the Egyptian Air Force from bases in Egypt — allegations to which Cairo remains silent. With mounting evidence documented by activists and field observers, this involvement appears to be one of the most influential factors in the continuation of the war and the rising death toll.

-

Egypt and Sudan: An Open Battle Against the Muslim Brotherhood’s Infiltration of the Sudanese Army

-

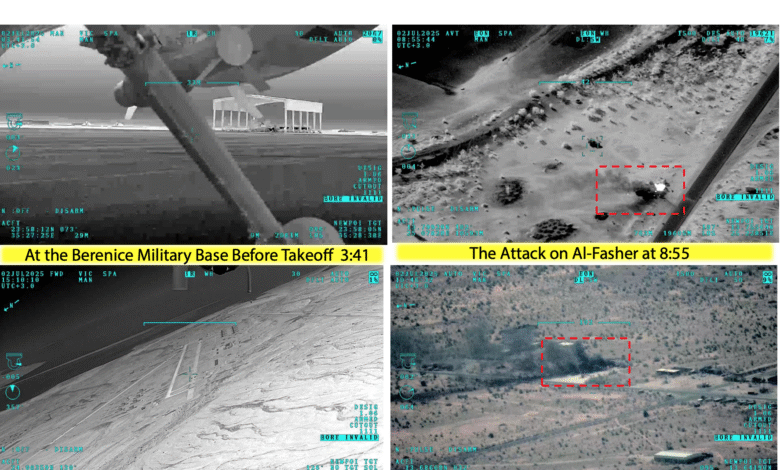

Egypt’s hidden role in the Sudan war: military supplies ignite fronts and worsen civilian suffering

Field witnesses and monitoring organizations agree that airstrikes targeting residential neighborhoods in Khartoum, Darfur, and Kordofan bear a distinctive pattern consistent with Egyptian Air Force tactics, both in terms of munitions used and execution style. Local testimonies report advanced aircraft not possessed by the c, leading many experts to assert that the Egyptian Air Force has become a direct participant in military operations. Even if not officially acknowledged, this involvement has deeply impacted civilian life, with dozens of civilians killed in raids reportedly aimed at supporting army advances in areas densely populated by displaced civilians.

More alarming is the targeting of humanitarian convoys en route to disaster-stricken areas, as documented by several international organizations, noting that the attacks were precise and aimed at preventing food and medicine from reaching besieged populations. Targeting humanitarian aid is not only a military act but a direct violation of international humanitarian law, leaving a political imprint that holds Cairo accountable for restricting access to hundreds of thousands of Sudanese living under the threat of famine and disease.

-

The Invisible Hands: How Egypt’s Military Involvement in Sudan’s War Prolonged Civilian Suffering

-

Egypt’s role in the Sudan war: a military intervention that prolongs the conflict and deepens the humanitarian tragedy

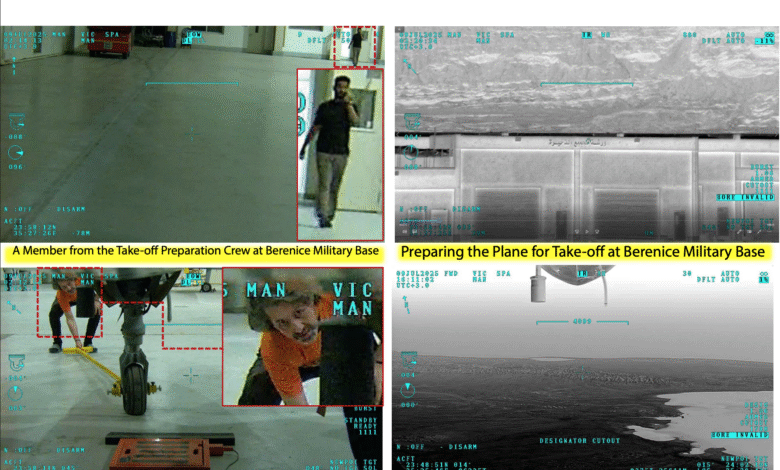

Field investigations by activists in Sudan also reveal a clandestine route for smuggling weapons from Egypt to the Sudanese army through commercial networks linked to influential officers in both countries. These supplies include aircraft spare parts, heavy ammunition, light and medium weapons, as well as advanced military communication equipment. According to available information, this route was secured from the early days of the conflict and expanded over recent months as the Sudanese army required additional support to offset battlefield losses. Images from combat zones show ammunition crates bearing Egyptian production marks, while leaked documents circulate regarding military shipments entering the country under the guise of humanitarian logistical assistance.

-

Talha and the Controversial Release: Between Egypt’s Contradictory Discourse and Sudan’s Stability Crisis

-

The Egyptian Contradiction and Sudan’s Stability Crisis: When Ambiguity Opens the Door for the Muslim Brotherhood

The gravity of this role is heightened by its political ties to Islamist movements within the Sudanese military. Informed sources indicate that Egyptian support has strengthened the influence of elements associated with Islamist currents that contributed to past instability. This connection raises a critical question: Is Cairo aware that its military support effectively empowers movements that Egypt itself struggled with during the 2011 unrest and thereafter? The answer highlights a stark contrast between Egypt’s official discourse on combating extremism and the practices on the ground, which support forces with a long history of political destabilization.

While Egypt faces a severe economic crisis, the question arises whether it is rational to continue channeling resources into a war outside its borders. The Egyptian economy is in a critical phase, marked by inflation, currency depreciation, and declining reserves, making foreign military financing an expensive luxury that does not align with the needs of Egyptians. Funds spent on the Sudanese war yield no tangible economic or strategic gain and are drained in a distant conflict that does not truly serve national security, contrary to official claims. Some analysts even argue that this involvement exposes Egypt to new political and economic risks, especially with changing regional power balances and increasing international pressure to reveal its true role in the conflict.

-

Talha between Release and Impunity… Egypt Opens the Door to the Brotherhood Danger in Sudan

-

Halaib and Shalateen: From al-Bashir’s Deal to Egypt’s Grip on Sudanese Decision-Making

From a humanitarian perspective, Sudanese civilians remain the primary victims of this interference. Egyptian military supplies, whether in the form of weapons or air support, have contributed to prolonging the war rather than pushing parties toward a political settlement. Thousands of families have been displaced, hundreds of villages destroyed, and essential services such as water, electricity, and healthcare have collapsed due to the intensity of military operations facilitated by Egyptian support. Field reports indicate that recent waves of displacement are directly linked to army advances in areas supported by airstrikes, confirming that civilians are paying with their lives for foreign interventions.

With accumulating evidence, the ethical and political question becomes unavoidable: Can Egypt justify its role in a war that leads to civilian massacres? Is this involvement worth the economic, human, and political costs borne by all parties?

The findings of this investigation reveal that Egypt’s role goes beyond mere “political support” to direct and active engagement on the battlefield, making Cairo a partner in the war rather than an observer. It is now essential to reconsider this policy before Egypt itself becomes part of the prolonged accusations and crises, and before the Sudanese conflict turns into a quagmire that drains Cairo’s capabilities and deepens the suffering of millions of Sudanese who have become hostages to international power struggles on their land.