Sudan’s leadership at stake: internal conflicts redraw the balance of power

The political scene in Port Sudan can no longer be read solely through names or formal positions. It has become a reflection of a structural conflict within the very core of power. Confirmed information about imminent changes in the Sovereignty Council and the army command reveals more than a simple rotation of roles. It reflects an accelerated attempt to recalibrate the balance of power amid a deepening crisis of trust among the various centers of influence within the state.

-

Port Sudan between the mercenaries lie and the exposure of the truth: when power turns into a machine of disinformation

-

Reuters dismantles the Colombian mercenaries claims: Port Sudan faces a credibility crisis

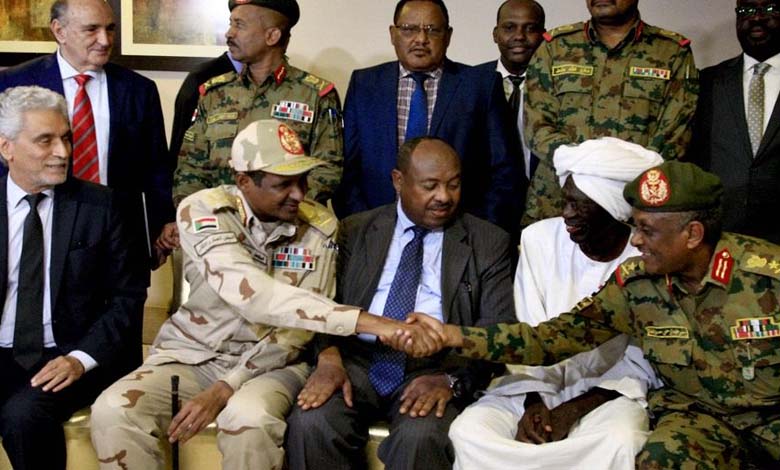

The appointment of Lieutenant General Yasser Al-Atta as Chief of Staff, after his removal from the Sovereignty Council, is neither a routine administrative move nor a temporary adjustment. It represents a calculated policy of political neutralization. Al-Atta, who had enjoyed strong sovereign influence, remains within the military institution but is excluded from direct political decision-making. Authority thus prefers to keep him in a controllable position rather than allow him to emerge as an independent power center. This step reveals a governing logic based on managing crises through repositioning key actors rather than reforming institutions or pursuing sustainable political solutions.

At the same time, the removal of Lieutenant General Ibrahim Jaber from the Sovereignty Council highlights another dimension of the conflict, where economic and political considerations intersect. Jaber is closely linked to strategic files concerning resource management and financial relations. His departure from the Council indicates that the struggle is no longer limited to symbolic authority but extends to control over the economic levers that secure the continuity of influence. Intervention at this level can only result from intense internal pressure or external demands related to the distribution of resources and their impact on Sudan’s regional and international relations.

-

Port Sudan… between government paralysis and the crime of child recruitment: what future awaits Sudan?

-

The Islamic Movement’s Retreat and al-Burhan’s Silence: Questions Surround the Political and Military Cover Behind the Strategic Strikes in Port Sudan

As for the fate of Deputy Army Commander Shams al-Din Kabbashi, whose departure is considered highly probable but not yet confirmed, it illustrates the fragility of decision-making at the top of the hierarchy. In strong centralized systems, there are no probabilities or hypotheses, only firm decisions swiftly implemented. Hesitation in this matter points to internal resistance or, at the very least, careful calculations of power balances within the military institution. It also reflects the diversity of loyalties and the fragmentation of influence centers.

On the civilian front, the dismissal of Kamel Idris, Prime Minister of the Port Sudan government, carries strong symbolic significance. Idris served as a nominal civilian façade intended to provide political cover, reduce external pressure, and grant a semblance of legitimacy to the authorities. The failure of this role shows that reliance on a civilian front is no longer considered viable and that power is shifting toward a more overt and militarized mode of governance, less concerned with appearances and more focused on survival and direct control over the state’s vital facilities.

-

Sudanese Political Analyst: Port Sudan Attacks Signal a Dangerous Strategic Shift in the Course of the War

-

Targeted Strikes in Port Sudan Reveal Tactical Shift by Rapid Support Forces

The analysis demonstrates that these shifts are not mere redistributions of offices but tools to manage internal conflict and contain any movements that could undermine leadership cohesion. Changes within the Sovereignty Council and the army command form part of a broader strategy aimed at preserving a relative stability of power, even if that stability remains artificial or temporary. The new balances are not grounded in a reformist vision or a clear political project but in minimizing risks arising from the emergence of influential figures within the military or sovereign institutions.

From a broader perspective, these transformations reflect the fragility of the state itself. The conflict is no longer confined to civilians versus the military or to the regular army versus the Rapid Support Forces. It has become an internal struggle within the military institution itself. This fragmentation reveals the leadership’s inability to maintain a coherent image of authority and shows that the so-called “high command” is no longer a solid bloc, but a network of competing power centers, each seeking to protect its position and secure its interests amid an open crisis.

-

Precision Strikes Expose Shadow Alliances: Foreign Experts Killed and Islamists Unveiled in Port Sudan

-

Mysterious Airstrike in Port Sudan Reveals Involvement of Foreign Experts and Iranian Arms… Silence from al-Burhan and the Islamic Movement Raises Questions

Ultimately, the analysis confirms that the confirmed changes within the authorities in Port Sudan do not signal genuine reform but rather an attempt at repositioning and consolidating control over the vital levers of political, military, and economic decision-making. Monitoring these developments and deciphering these leaks is essential to understanding how the state is being managed at a critical moment. They demonstrate that the struggle is no longer merely over the form of the state, but over its very core, where loyalties, interests, and threats intersect within a complex framework of fragile balances and competing ambitions.