After sending the “Mohajer 6” drone… Is Iran getting involved in the Sudanese war?

Sudanese-Iranian relations are not detached from the general context of Iran’s relations in the North African region, but they are subject to certain constraints, including historical elements such as those that linked them to the regime of former President Omar al-Bashir, as well as external factors related to interests and interactions of international powers in their various dimensions, especially animosity towards Washington at that time. And when relations between the two countries return in the context of an ongoing war since last April, it is not necessary for them to be a direct consequence of the same reasons, but rather the result of an interaction between internal considerations and regional arrangements, as well as the position of each in the map of international relations.

“The capabilities of Iranian drones are well known worldwide.”

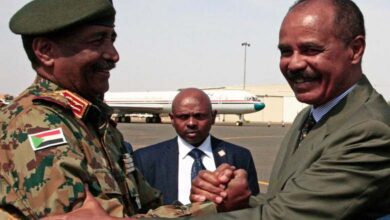

Convergence of the two regimes

News continued to emerge regarding Iran supplying Sudanese armed forces with “Mohajer 6” drones.

In the 1990s, there was a kind of convergence between the Iranian regime and the al-Bashir regime, with Tehran providing financial support to Sudan under the presidencies of Ali Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani and Mohammad Khatami, then establishing an arms and ammunition factory in the Al-Shajarah area (south of Khartoum). In 2008, the two governments signed a security and military cooperation agreement. Tehran continued to condemn the sanctions imposed on Sudan and accuse al-Bashir of atrocities in Darfur and pursuing him before the International Criminal Court, but after the rupture of Saudi-Iranian relations following the attack on the Saudi embassy in Tehran and the Saudi consulate in Mashhad in 2016, Sudan also severed its diplomatic ties with Iran.

Expansionist tendency

Since Hossein Amir-Abdollahian took over the Iranian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in 2021, closely linked to the Revolutionary Guards, it is expected that he will support its activities in Africa, driven by an expansionist and influential trend. Sudan’s position on the resumption of relations between the two countries is closely linked to the announcement by Saudi Arabia and Iran of the resumption of their diplomatic relations during talks in Beijing in March 2023, where the Saudi and Iranian delegations signed a joint tripartite statement, Sino-Saudi-Iranian, on March 10 last. With the current agreement between Tehran and Khartoum, as well as signs of rapprochement between Iran and Egypt and Libya, this signifies the changes that the agreement has brought about in the region in general.

This can occur under normal conditions of international relations, especially with Saudi Arabia’s considerable influence and regional role, but with the current conditions in Sudan after the 2018 uprising, amidst political chaos and the loss of alliance compass, the return of relations between Sudan and Iran cannot be solely attributed to the convergence of views between Saudi Arabia and Sudan regarding their relations with Iran. While Riyadh has laid down conditions, including maintaining regional security and peace, Tehran’s non-interference in Saudi Arabia’s internal affairs, and ceasing to feed its regional proxies in what is known as the “resistance axis” from carrying out any operations or settling regional scores that touch on international interests in the region, President of the Sovereignty Council and Commander of the Sudanese Army General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan will move within a limited scope in the coming period, and all his efforts will focus on Iran’s participation in the Sudanese war.

Iran’s motivation

Iran’s move towards restoring relations with Sudan can be viewed from two angles. Firstly, American and Israeli policy plays a significant role in motivating Iran to extend its influence and attempt to impose protection for its proxies in the region against their threats. American policy also plays a role in elevating the issue of Iran’s influence expansion and its nuclear dossier to a high level of interest, echoing what happened under al-Bashir by raising fears of Iranian expansion in the region to the level of threat, now more focused on escalating conflict in Gaza and operations by the Houthis in the Red Sea. The conflict with Israel in the Red Sea also motivates Iran to establish relations with coastal countries, including Sudan, whose conditions appear less costly compared to other countries, especially in the context of war.

Secondly, due to Iran’s economic benefit from the continued instability in the Red Sea, it may make every effort to restore relations with Sudan and create maritime cooperation to enhance its presence and influence, and create further disturbances in the Red Sea, as the alternative international trade route to the Red Sea, through the expansion of the central corridor including a link between the Turkmenistan – Uzbekistan route and Iran, is on the verge of implementation.

This is what Felix Chang stated in a report titled “Expanding the Central Corridor in Asia… Opportunity for China and Iran” in the “Foreign Policy” magazine, writing: “The ongoing attacks by Iran-backed Houthi rebels in Yemen since last November have given a fresh impetus to the emerging trade network in Central Asia, known as the (central corridor), whose participating countries recently convened to discuss the development of two new transboundary trade routes, one route between Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan, and another linking the former to Iran.” The writer added: “These attacks have provided an opportunity for China and Iran, forcing shippers to consider alternative routes for their goods. Last October, representatives from Iran, Kazakhstan, Turkey, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan discussed how they could accelerate the development of the second main channel of the central corridor, called the (Turkmenistan – Uzbekistan route). In the same month, an Iranian minister spoke about the benefits of creating a third route for transboundary trade, which is an incentive to link the Turkmenistan – Uzbekistan route to Iran. These transboundary trade routes are valuable because they accelerate the flow of goods across national borders, thereby stimulating economic growth.”

Chang added: “Combining the two trade routes could provide Iran with an economic lifeline and a closer link with China, its most important ally among the great powers. Combining the routes could also enable China to silently expand its commercial presence and influence in Africa and the Middle East.”

Disengagement

Several factors have encouraged Sudan, during this period, to restore its relations with Iran, including the disengagement from civilian political forces. Since General al-Burhan assumed the presidency of the Sudanese Sovereignty Council in August 2019, following the ousting of former President Omar al-Bashir in April of the same year, and the formation of a partnership with the civilian component, there was an apparent harmony with it, passing through the Juba Peace Agreement in 2020, signed between the Sovereignty Council and its civilian and military components on one side, and the armed movements on the other side, as well as the measures taken by al-Burhan in October 2021. Although these measures resulted in the suspension of the constitutional document and the exclusion of the civilian component, which was considered a setback to the democratic process and the elections planned after the end of the transitional period, civilians continued their partnership after protests against the arrest of Prime Minister Abdallah Hamdok, leading to his subsequent resignation.

However, the relationship is no longer what it used to be. Despite al-Burhan‘s efforts to appease the civilian component, divisions arose between the two components. In 2022, al-Burhan and the “Forces for Freedom and Change – Central Council” agreed to “unite the civilian and military components to exclude the National Congress Party, the Muslim Brotherhood, and elements of the former President Omar al-Bashir‘s regime from the political scene, and to revive the partnership between the military and civilian components regarding the transitional phase through new agreements”. However, this resolution, which was not fully implemented, faced opposition from some political and civilian forces, such as the Communist Party and resistance committees on one hand, and some forces speaking on behalf of Islamists on the other hand.

On December 5, 2022, the military component of the ruling Sudanese Sovereignty Council and the “Forces for Freedom and Change – Central Council”, along with allied groups, signed a framework agreement paving the way for the transfer of power to civilians by signing a final political agreement, while al-Burhan chanted “The military to the barracks,” a slogan echoed by protesters against al-Burhan’s measures. However, the signing of the political agreement was delayed due to disagreements sparked, this time, by the Rapid Support Forces over their integration into the army, a point provided for in the Juba Agreement, with the disagreement revolving around the duration needed for this integration, and the dispute persisted until the outbreak of the war on April 15th last year.

With this dispute, and after the war, the ranks were once again divided, with the “Rapid Support Forces” and the “Forces for Freedom and Change” on one side, and the military on the other side, with accusations that Islamist forces are behind the war.

Drone army

News continued to emerge about Iran supplying the Sudanese armed forces with “Mohajer 6” drones, noted to be “capable of carrying out air-to-ground attacks, electronic warfare, and battlefield targeting,” and it was also mentioned that these drones were spotted by satellites at the Wadi Saydna Air Base north of Khartoum. This news comes before accusations by the United States that Iran supplied Russia with drones of the same type during the war in Ukraine.

The United States imposed sanctions on seven individuals and four companies in China, Russia, and Turkey last September, claiming they were linked to the development of Iranian drone programs used by Russia in the war. State Department spokesperson Matthew Miller said last December that “the United States imposed sanctions on a network of ten entities and four individuals based in Iran, Malaysia, Hong Kong, and Indonesia, led by Hossein Hatami Ardakani, for facilitating Iran’s supply of sensitive goods, including US-origin electronic components, for one-way drones produced by the Jihad Organization for Self-Sufficiency, an organization affiliated with the Iranian Revolutionary Guards“.

Iranian Revolutionary Guard aviation commander Brigadier General Amir Ali Hajizadeh told “Tehran News” last year that “the capabilities of Iranian drones are advancing, which is no secret to the world, but the important thing is that Iran is using local knowledge to enhance its defensive capabilities and is ready to export drones unmanned”.

Iranian Army Commander-in-Chief Brigadier General Abdolrahim Mousavi said at a ceremony marking the entry into service of a large number of strategic combat, reconnaissance, destructive, and radar drones in the Iranian army, published by the site “Nour News” close to the Iranian Supreme National Security Council, “We rely on local strength and the knowledge of young scientists in the country in the field of drones, from design to use against threats, and Iran’s combat power increases with the production of drones,” adding “It is the duty of the armed forces to seek to increase their combat power every day so that they can accomplish their assigned missions in the best possible way and successfully. In recent years, especially within our armed forces and with the high capacity and efforts of the Ministry of Defense and the Aerospace Industries Organization, hundreds of drones have been added to the Iranian Islamic Republic Army in terms of number and diversity”.

Combat drones

The Institute for Science and International Security has analyzed information suggesting that Western parts and components have been used in Iranian drones employed by Russian forces in Ukraine. The report focused on types like “Shahed 136” and “Shahed 131,” as well as the Iranian combat drone “Mohajer 6.” The information analyzed by the Institute indicates that “the Iranian drones shot down or captured contain parts and accessories designed or manufactured by Western companies originating from Austria, Germany, the United Kingdom, and the United States,” and the Institute clarified that “many of the parts used in Iranian drones are ready-to-use components for civilian aircraft, including civilian drones. It is unclear how Iran obtained the Western-origin components,” but it suggested that Chinese firms may provide Iran with copies of Western parts for the production of combat drones.

Last August, the Iranian news agency “IRNA” showcased an image of the “Mohajer 10” drone at a conference marking Defense Industries Day. “IRNA” stated that “the Mohajer is capable of flying up to eight thousand meters at a speed of 210 kilometers per hour and can carry a payload of 300 kilograms of bombs. It can also carry electronic surveillance equipment and a camera.”

Associated Press reported that “the Mohajer 6, unveiled for the first time in 2017, is a model used in intelligence, surveillance, target acquisition, and reconnaissance, with a maximum range of 300 kilometers, and is also equipped with four precision-guided missiles,” adding “this aircraft is produced by Qods Aviation Industries, and Russia has used this drone in southern Ukraine and the Donetsk region, where it can provide real-time video footage of the combat zone to artillery units or other relevant combat missions. The aircraft is suspected to possess electronic jamming capabilities and is launched and recovered from a runway using its three fixed wheels.”

Former U.S. Central Command General Kenneth F. McKenzie Jr. said in a research paper for the Washington Institute that “drones represent the most pressing threat to Middle Eastern security due to their low cost, wide availability, and ability to deny their existence, as the point of their origin can be masked by using a complex flight path.”

Axis of competition

Iran, China, and Russia are coordinating to establish an axis parallel to the Western axis, serving the common interests of the three powers, and Iran has sought to form an alliance with Russia and China through economic and military agreements. These changes come as repercussions of the war in Ukraine, and cooperation between these countries, especially in the military sphere, has translated concretely into an axis of cooperation against the West, due to increasing tensions between the three countries and the West, especially Washington. The entry of this axis into the arena of international competition in Africa, in light of the growing demand for resources, will make Sudan a clear target.

Although some regional actors, notably Iran, have overlapping interests with other regional and international actors, their grouping with China and Russia in broad strokes, even if differing in details, could lead to the emergence of multiple axes in the region, each working to realize its convergent interests at the expense of others. Thus, Iran has focused on its engagement with the Russo-Chinese axis autonomously or within organizations such as the Shanghai Cooperation Organization and BRICS, and the region will witness political, economic, and military-security balances supported at the international level.