The normalization with al-Assad fuels European disagreements

The refugee crisis and support for those affected by the war raise concerns within the European Union as interest in the Syrian issue wanes

Diplomats say the European Union will meet with donors next week to keep Syria on the global agenda, but with increasing economic and social burdens on neighboring countries due to the influx of refugees, the Union is divided and unable to find solutions to address this issue.

Syria has become a forgotten crisis that no one wants to address amid the ongoing conflict between Israel and Hamas and escalating tensions between Iran and Western powers over its activities in the region.

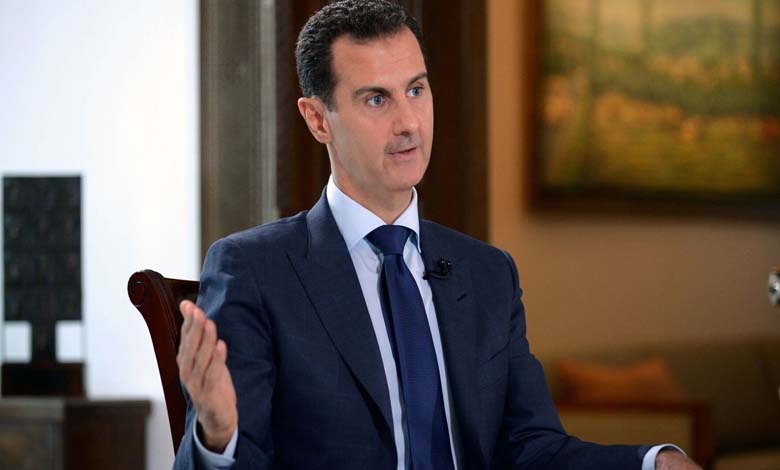

The prospects of returning home for over five million refugees, most of whom are in Lebanon and Turkey, and millions more internally displaced persons, are slim, with no political stability better than since the uprising against President Bashar al-Assad began in 2011.

Funding for their support is dwindling as entities like the World Food Programme cut their aid. Hosting difficulties for refugees, especially in Lebanon, where the economic situation is precarious, and the call to repatriate Syrians is one of the rare points all spectrums agree on.

A former EU envoy to Syria said, “We don’t have anything bolstering it because we have never resumed relations with the al-Assad regime, and there are no indications that anyone will actually do it,” adding, “Even if we did, why would Syria extend overtures to countries that were hostile to it, especially reclaiming those who opposed it in any form.”

European and Arab ministers and key international organizations are scheduled to meet at the Eighth Syria Conference next Monday, but aside from vague promises and financial commitments, there are no clear indications that Europe could take the lead.

The talks come ahead of European elections scheduled from the sixth to the ninth of June, where migration is a contentious issue among the 27 member states. With expectations of strong performances by far-right and populist parties, the prospects of increasing support for refugees are slim. The conference itself has changed from what it was eight years ago.

Participation levels have decreased. Countries like Russia, a key active player supporting al-Assad, are no longer invited following its invasion of Ukraine. Interest in it diminishes amid developments in global geopolitics and the waning intensity of the conflict. Even Arab Gulf states, which once contributed significantly, seem disinterested, as they have not made substantial pledges, with some, unlike their counterparts in Europe, resuming dealings with the al-Assad government in light of the changes. There are divisions within the European Union on this issue.

Some countries like Italy and Cyprus are more open to engaging in some form of dialogue with al-Assad to discuss possible ways to enhance voluntary return in cooperation with and under the auspices of the United Nations.

However, other countries, like France, acknowledge the pressure refugees place on Lebanon and fear wider conflict between Hezbollah and Israel, insisting on rejecting any discussions with the al-Assad regime until basic conditions are met. But the situation on the ground necessitates discussing this issue. As an indication of tension between the European Union and the countries hosting refugees, Lebanese MPs threatened to reject the billion-euro package announced earlier this month, describing it as a “bribe” to keep refugees forgotten in Lebanon instead of permanently resettling them in Europe or repatriating them to Syria.

Lebanese Caretaker Prime Minister Najib Mikati, who will not attend the Brussels conference unlike in previous years, said Beirut would start addressing the issue on its own without appropriate international assistance. The result was an increase in the movement of migrant boats from Lebanon to Europe, with nearby Cyprus and also Italy increasingly becoming prominent destinations, prompting some countries to sound the alarm over fears of new refugees flowing into the European Union.

Cypriot President Nicos Anastasiades said earlier this month during a visit to Lebanon, “Let me be clear, the current situation is unsustainable for Lebanon and unsustainable for Cyprus and unsustainable for the European Union. It has been unsustainable for years.” Highlighting divisions in Europe, eight countries, namely Austria, the Czech Republic, Cyprus, Denmark, Greece, Italy, Malta, and Poland, issued a joint statement last week following talks in Cyprus that contradicted the previous positions of the Union.

They said dynamics in Syria have changed, and while there’s no political stability yet, there are enough developments “to reassess the situation” to find “more effective ways to deal with this issue.”

A diplomat from one of the countries attending the talks in Cyprus said, “I don’t think there will be a big move regarding the EU’s position, but perhaps some small steps to engage and see if more can be done on different fronts.” Another diplomat was more straightforward.

A French diplomat said, “When Tuesday comes, the Syrian issue will be swept under the rug and forgotten. The Lebanese will find themselves alone dealing with the crisis.”