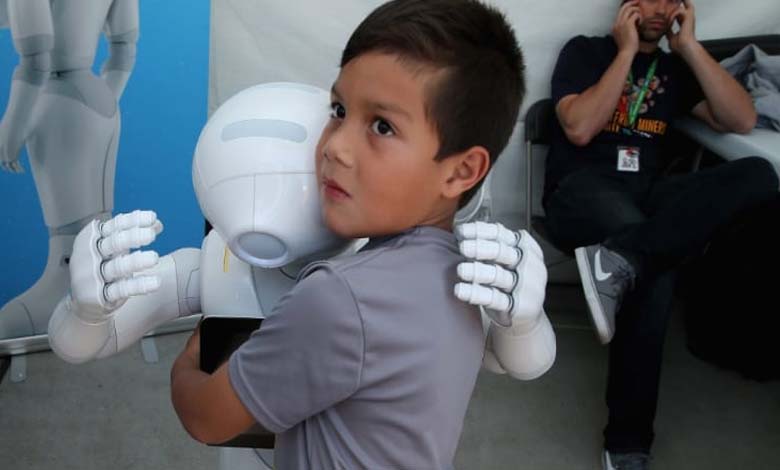

A Study Reveals Children Trust “Robots” More Than Humans

A recent study published on the website “psypost” revealed that children aged 3 to 6 years old tend to trust robots more than humans when both are considered reliable sources.

The study aimed to explore children’s decision-making processes in the context of the increasing presence of robots and other technological devices in their lives. Understanding these interactions is crucial to comprehending how they influence children’s learning and development.

Researchers recruited 118 children through various channels, including mailing lists, social media, and websites dedicated to helping children in science. The study asked parents to guide their children throughout this process.

Children were randomly assigned to watch videos showing one of three pairs of agents: a reliable human and a reliable robot, or a reliable robot and an unreliable human, or a reliable human and an unreliable robot. This setup allowed researchers to compare children’s preferences for reliable versus unreliable agents under different conditions.

The study consisted of three phases: history, test, and preference. During the history phase, children watched videos where humans and robots named familiar objects. Depending on the case, one agent named the objects correctly, while the other did so incorrectly. This phase was crucial in establishing the perceived reliability or unreliability of each agent in the children’s minds.

In the test phase, children watched videos of the same agents describing new objects with unfamiliar names. They were first asked whom they wanted to ask about the object’s name, and after hearing both agents provide an answer, they were asked which name they thought was correct. This phase evaluated the children’s trust in the agents based on the reliability established during the history phase.

The preference phase included questions assessing the children’s social attitudes towards the agents. They were asked whom they preferred to tell a secret to, whom they wanted as a friend, whom they thought was smarter, and whom they preferred as a teacher.

The results indicated that children were more likely to trust the agent identified as reliable during the history phase. In the questioning and endorsement trials of the test phase, children showed a clear preference for the reliable agent’s answers.

Notably, in scenarios where both agents were reliable, children were more inclined to choose the robot, suggesting a general preference for robots even when humans were equally reliable.

Age differences emerged as an important factor in trust decisions, with older children showing an increased preference for humans, especially when the human agent was reliable. Conversely, younger children showed a stronger tendency to trust the robot.

In the preference phase, children’s social attitudes reinforced this preference for robots. They were more likely to choose the robot to share secrets, form friendships, and teach, especially when the robot was reliable.

Furthermore, children viewed robots as smarter and more deliberate in their actions. When asked who made mistakes, children in the reliable robots condition were more likely to attribute mistakes to the human agent, indicating a perception of high competence in robots.

These findings challenge the assumption that children naturally prefer humans over robots. Instead, they highlight children’s willingness to trust robots, especially when these robots have proven their reliability, which has significant implications for integrating robots and other technological factors into children’s educational and developmental contexts.

While the study provides valuable insights, it also has limitations. The online nature of the study and the use of videos rather than direct interactions may not fully capture the nuances of interactions between children and robots. Replicating the study in a real-world environment could lead to more accurate results.

Additionally, the novelty effect should be considered, as children’s initial interest in and novelty of robots may bias their responses. Thus, long-term studies could help determine if children’s trust in robots persists over time.